FOIMan summarises what you need to know about data protection laws.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR – Regulation (EU) 2016/679 to give it its official nomenclature) entered into force in 2016 and has fully applied since 25 May 2018.

BREXIT will not kill GDPR

On the day that the UK leaves the European Union, all of EU law will be absorbed into UK law. The National Archives have done a great job of reflecting that in the legislation.gov.uk website, where you can now find all EU law that will apply. Over time, the UK government and Parliament will repeal EU laws as required. GDPR is no different. Until and unless the UK government repeals it, it continues to apply in the UK.

That said, the government has passed regulations which will amend GDPR on the day that we leave and create something called ‘UK GDPR’. Effectively what the regulations do is remove references that no longer make sense once the UK leaves the EU, such as references to Euros and European institutions. So BREXIT will change GDPR – but not in any great substance in respect of its day-to-day application.

What does GDPR do?

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) does what it says on the tin – it regulates for data protection. This means that it sets out the rules which apply to any legal entity in the EU/UK that uses data relating to individuals. Even bodies outside the EU and UK have to comply with those rules if they handle data about individuals in the EU or UK. It also sets out individuals’ (extensive) rights in relation to this data. This data is referred to as personal data.

So why do we have the Data Protection Act 2018?

Think of GDPR as being like a Swiss cheese – it’s full of holes. Wherever the members of the EU couldn’t agree on how the law should work, or where they simply felt that it was appropriate for countries to decide what they did in certain areas, GDPR left it to member states to fill in the gaps. In the UK this was done with the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA). Examples of gaps filled by the DPA are:

- rules for bodies (like the police) that have powers to investigate and prosecute crime setting out how they should handle personal data relating to those activities (implementing a separate EU Law Enforcement Directive)

- the exemptions and restrictions relating to the rights that individuals have under GDPR

- the legal justifications for handling certain ‘special category’ (sensitive) personal data.

DPA filled in all these gaps, and also amended other legislation to ensure that GDPR and the DPA could be incorporated into the existing body of UK law.

What is personal data?

GDPR (and the DPA) set out the rules for handling personal data. Personal data is ‘any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person’ (GDPR Art. 4). Natural person just means ‘individual’ in this context, as opposed to a ‘legal person’ which can be any legal entity – including government departments and multinational corporations. The really important word here is ‘identifiable’. This means that information can be personal data even if we can’t immediately identify who the person it relates to is. As long as we have the means to identify them – perhaps a key, or institutional knowledge – then it will be personal data. A photograph can be personal data even if it doesn’t have a name attached to it.

- identifiers: it’s worth noting that lots of things count as ways to identify somebody under GDPR. Certainly someone can be identified by their name, but they can also be identified by their location (‘that blob on the map there is walking up the high street’) or their web address (‘the person using that computer has been looking at some…ahem, interesting websites’). This means that personal data covers a very broad range of information in practice.

- ‘relating to’: to be personal data it needs to relate to somebody. Often it’s obvious that information relates to an individual, but sometimes it’s not. Take the photograph mentioned above. Someone could appear in a photo of a street scene taken to illustrate a report on street clutter in the high street. The report focusses on the fact that the street is cluttered, and the photo is simply used to illustrate that. However, let’s say the individual’s manager is reading the report and recognises them in the photo. The photo is dated and seems to show that the individual was in the street when they were supposed to be elsewhere. If the manager uses the photo as evidence to take disciplinary action against the individual, the photo now relates to them in a way it didn’t when they were just an incidental passer-by in the street scene. The photo has become personal data because of how it is used.

- format: for the most part it doesn’t matter what form information relating to an individual is in. Electronically held data relating to someone can be personal data, but so can paper files in any form of structure. Even ‘unstructured manual data’ – loose notes, for example – can be personal data if it is held by public bodies in the UK.

What are data controllers?

Firstly, what data controllers are not. They are not – usually – individuals. In a business or public authority there may be someone with responsibility for leading on data protection compliance – but whatever they’re called, they are not data controllers (at least as far as GDPR is concerned). Data controllers are the legal entity that decides how the data will be used – in most situations, this means that data controller means ‘the organisation’. Only where the legal entity = one individual is that person the data controller. For example, I am a sole trader, so Paul Gibbons is a data controller – there isn’t anyone else, and there is no legal entity beyond me. That’s not the case for businesses, public bodies, charities, etc. It is the organisation that is the data controller. The organisation is responsible for compliance with GDPR, not an individual.

What do these data protection laws require us to do?

At their simplest, GDPR and DPA require data controllers to ensure that their handling of personal data is consistent with the data protection principles. The graphic illustrates these principles.

At their simplest, GDPR and DPA require data controllers to ensure that their handling of personal data is consistent with the data protection principles. The graphic illustrates these principles.

- lawful, transparent and fair: can the use of the data be justified using one of the options listed at Art.6 of GDPR (and for special category data, Art.9 as well), and has the individual been told how their data will be used?

- purpose limitation: the data will only be used for the reason specified at the start

- minimisation: only the data required will be used and no more

- accuracy: data will be kept up-to-date and accurate

- storage limitation: data won’t be kept longer than necessary

- integrity and confidentiality: data will be kept securely

- accountability: the biggest change under GDPR – the data controller must be able to prove that they’ve taken steps to achieve compliance with the above; so for example, they’ve put in place a procedure to check that individuals’ contact details are up-to-date.

What rights do people have?

Individuals have more rights than they used to. These rights include the right to:

Individuals have more rights than they used to. These rights include the right to:

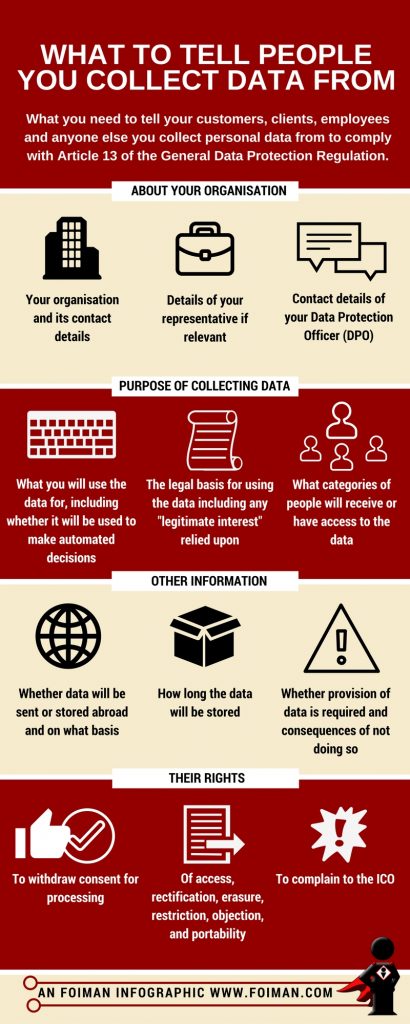

- transparency: the right to be told what data is being collected about them and why. The graphic here illustrates what individuals have to be told, usually in what is commonly known as a ‘privacy notice’.

- access personal data (or ‘subject access’)

- rectify incorrect personal data

- object to, restrict use of or erase personal data

- object to direct marketing

- have personal data transferred to another body

- be able to challenge decisions made by a computer.

Most of these rights are qualified – i.e. there are exemptions that restrict them in some circumstances.

What responsibilities do organisations have?

GDPR requires data controllers to act in a way that is consistent with the data protection principles. In some cases it goes beyond these though and requires specific actions to be taken.

- public bodies and some other organisations must appoint someone to act as a mini-Commissioner on the ground (i.e. they provide advice to the data controller, monitor compliance, and act as the Commissioner’s contact point) called a Data Protection Officer

- most organisations must maintain a ‘record of processing’ – basically a register of personal data and how it is used

- contracts with organisations that handle personal data on the controller’s behalf must contain certain provisions to ensure that GDPR can’t be contracted out of

- the risk of security breaches must be assessed and appropriate security safeguards put in place

- data security breaches must be reported to the ICO within 72 hours in specified circumstances

- the impact on compliance with GDPR must be assessed before starting to handle personal data in specified circumstances (a Data Protection Impact Assessment)

- a condition must be met before transferring personal data outside the EU/UK.

What happens if we fail to comply with data protection laws?

The Information Commissioner has lots of powers to enforce data protection laws. These include significant fines as you’ve probably heard, but also the ability to force organisations to stop handling data if it is being used in a way that breaches GDPR. In certain circumstances, individuals can seek compensation from organisations if a breach of data protection laws causes them problems or distress.